Bloomberg Businessweek

How States Are Shifting College Costs to Students

Beneath the ever-rising mountain of student debt lies a core question of

values and priorities. College degrees benefit both students and society,

providing paths to higher personal incomes and broader economic growth—but whofs

responsible for covering the cost of that investment? A new report shows how in

many ways, states have already answered that question. Theyfre passing the bill

on to families rather than to taxpayers at large.

The Chronicle of Higher Educationfs report

looks at the decades-long erosion of support for higher education. It charts how

public colleges were once seen as gworthy of collective investment for the

greater goodh but increasingly have been viewed as just benefiting individual

students, who gought to foot the bill themselves.h

This shift in public attitudes goes hand in hand with declining state support

for schools, both reflecting tighter budgets and changing priorities about

whatfs worthy of funding. The Chronicle reports

how, for example, a victory for auto dealers in South Carolina imposing a cap on

sales taxes cost the state gan estimated $169 million last year, which would be

sufficient to restore about half of the cuts made to public colleges since

2008.h

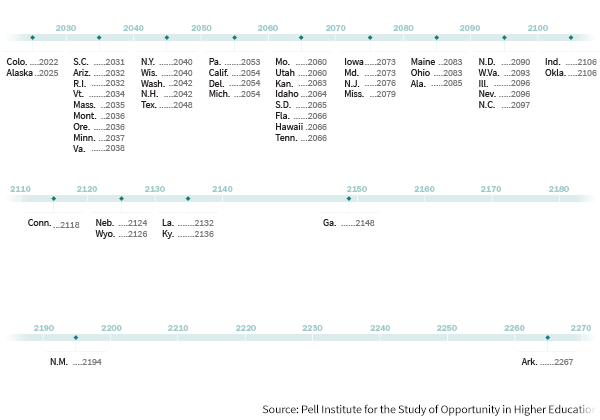

The report also highlights analysis

from the the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education

that shows if the funding trends since 1980 continue, some states could stop

supporting higher ed entirely within the decade. Colorado could be first,

reaching $0 in 2022, followed by Alaska two years later. In the 2030s, another

nine states could join them, including Virginia, Massachusetts, and Oregon.

Herefs the Chroniclefs chart showing

the timeline when funding could dry up in different places:

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Despite tales of rock climbing walls and bloated administrations, public

colleges overall havenft

changed over the past two decades how much they spend to educate each

student. With costs flat, public funding down, and public colleges asking

students to fund the shortfall in revenue, the education inequality gap will

further widen, the Chronicle argues.

That means leaving behind students who would have gone to college, found good

jobs, started businesses, paid taxes, and generally helped to drive the economy.

An undereducated workforce isnft cheap. States that think theyfre saving money

by saying higher education is a personal rather than collective investment will

wind up paying for the consequences.

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Weise

is a reporter for

Bloomberg Businessweek in New York. Follow her on

Twitter

@kyweise.